| |

Leprosy Mailing List – November 29, 2019

Ref.: (LML) Reducing transmission in poor hyperendemic areas - evidence from Uele (DRC)

From: Joel Almeida, London and Mumbai

Dear Pieter and colleagues,

A remarkably effective attempt was made in the Uele region (in the north-eastern part of what once was called Zaire, now Democratic Republic of Congo) to reduce transmission using anti-microbials,(1) without segregation and during a time of declining GDP per capita. The initial number of unregistered cases was 22/10,000 population.

The control programme

Patients self-reported for diagnosis, skin smears and skin biopsies were taken. Patients then continued living at home, without segregation. Mobile HD teams visited patients at fixed sites, at monthly intervals. Once a year patients at each site were visited by a physician. Training, re-training and supervision of HD paramedical workers was provided by an HD centre. This centre also provided in-patient treatment as necessary, orthotics, rehabilitation and research facilities. The anti-microbial chemotherapy is described later.

The socio-economic background

GDP per capita was low and declining.

Figure 1. Real GDP per capita in DRC, 1960-2018 (source: Trading Economics)

A steep decline in GDP per capita began in about 1975 and then temporarily levelled off until about 1990. Later GDP declined again.

The outcomes

The outcomes are shown below, starting in 1975. This was just after the HD control programme had gone through a decade-long transition period owing to political changes. From 1975 the mobile HD teams were more numerous, better equipped and better trained.

Figure 2. Newly detected patients with MB HD/100,000 population /year, 1975-1988 in Uele, DRC. (Almeida J 2019, based on ref 1)

The raw observations show a decline in newly detected MB patients. The "absence of mutilations" among newly diagnosed patients throughout the period was noted. MB patients formed fewer than 16% of all newly diagnosed patients.

It is useful to look at the period from 1978 onwards (year 4 in Fig. 2). By then any backlog of unregistered MB patients accumulated prior to 1975 was likely to have been registered.

Figure 3. Newly detected patients with MB HD /100,000 population /year, 1978-1981 in Uele (DRC), using prolonged anti-microbial protection (dapsone) for MB patients (Almeida J 2019, based on Tonglet et al, ref 1)

The decline in newly detected MB patients was rapid (about 17%/year). This occurred without increase in GDP per capita and without segregation of HD patients.

Prolonged anti-microbial protection with dapsone was used until 1981. During 1981, closely supervised 1-year experimental multi-drug regimens (including 6 months of daily rifampicin) were introduced for MB patients.

Figure 4. Newly detected patients with MB HD / 100,000 population / year, 1978-1981 in Uele (DRC), using 1-year multiple drug regimens including daily rifampicin. (Almeida J 2019, based on Tonglet et al, ref. 1)

The decline in newly detected MB patients slowed down once prolonged anti-microbial protection was withdrawn. 1 year of anti-microbial protection, despite including daily rifampicin for 6 months, did not suffice to maintain the earlier rapid decline of HD.

Was the decline only apparent rather than real? In 1984 total population surveys were done in 2 towns of the Uele area. Individuals were examined by an experienced paramedical worker and a doctor. No new MB patient was found among about 20,000 persons examined. Apparently not many MB patients remained unregistered. By contrast, nomadic people in an isolated part of the Uele area were found in 1984 to have a high prevalence of HD of about 460 per 10,000 population. This was similar to the prevalence of HD in the general population prior to the introduction of effective anti-microbial chemotherapy in the 1950s. (1)

Discussion

This evidence of rapid decline in HD with prolonged anti-microbial protection bears similarities to the observed rapid decline of HD in Shandong (China).(2, 3)

Figure 5. New case detection rate in Wenshan/Yunnan (upper line) and Weifang/Shandong (lower line), China. (Almeida J, 2019 based on Li et al, ref 2)

Figure 6. New MB cases detected over time in Shandong province, China. 1955-1983. (Almeida J, 2019 based on Li et al, ref 3)

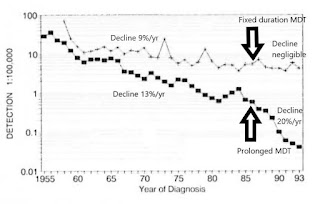

The evidence from Uele post-1981 and Yunnan post-1986, with a levelling-off in the decline of new HD patients, indicate the crucial importance of prolonged anti-microbial protection for MB patients. Both places also used BCG from the 1970s, as did Shandong.

All these observations above can be explained in important part by the following.

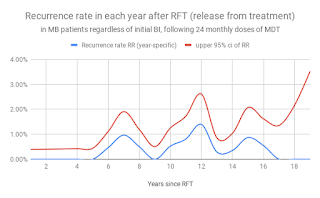

Figure 7. Recurrence rate among MB patients in each year following release from 24 months of MDT (Almeida J 2019, based on Balagon et al, ref 4)

Recurrence of disease among LLp patients is relatively frequent 6 or more years after 24 months of MDT. Recurrence can occur by endogenous relapse or exogenous re-infection, and is currently a central fact of the epidemiology of HD. This central fact cannot be ignored safely, otherwise our outcomes are likely to be disappointing and our predictions and models unrealistic.

Figure 8. Newly detected MB patients over time, worldwide. 1985-2017 (Almeida J, 2019, based on WHO, Weekly Epidemiological Records). Fixed duration 1-year anti-microbial protection mostly replaced prolonged anti-microbial protection by the year 2000. Since the late 1990s, the definition of MB has remained constant.

Recurrence among LLp patients after MDT is apparently keeping the HD endemic alive. It is also exposing the unfortunate individuals to avoidable damage. It is a major reason why children continue to develop HD. This gap in our defences undermines all our other worthy efforts to interrupt transmission, such as active case-finding, contact tracing, BCG vaccination and MDT.

The emerging picture of the epidemiology of HD in Figure 9 helps explain observations, including previously unexplained features of transmission including in affluent countries. That can be discussed in more detail at another time.

Figure 9. Epidemiology of Hansen's Disease for interruption of transmission. (Almeida J, 2019)

Implications for action

Our effective response can be to protect LLp patients against recurrence. This can be achieved with post-MDT chemoprophylaxis for all LL patients. That will shut down a major source of concentrated viable bacilli. As the evidence from prolonged anti-microbial protection in Uele and Shandong shows, it is more effective to treat the source of infection than to allow that source to continue. Looking for those infected by the source is helpful, but it is not as effective as shutting down the source. Just as looking for smoke is helpful in fighting fires, but putting out the fire is even more effective. (See also LML 4 Nov 2019, 18 Sept 2019, 9 July 2019)

Post-MDT chemoprophylaxis for LL patients is the critical intervention that can shut down a major neglected source of concentrated viable HD bacilli. That can open the door to a rapid decline in HD leading to near-zero transmission. It is also an essential part of competent case management, helping to protect the individual patient from avoidable damage. The evidence from Uele can embolden even the poorest hyperendemic area to strive for interruption of transmission, although increases in income would be highly desirable. Our improvements in field programmes can be from a springboard of demonstrable success. If we improve on the Uele approach by including active search for LL patients and contact tracing, we might achieve an even more rapid decline in HD than 17% to 20%/year. Whatever else we do or fail to do, let's include post-MDT chemoprophylaxis for LL patients so that we can end HD.

Joel Almeida

Translations

सभी एलएल रोगियों के लिए पोस्ट-एमडीटी केमोप्रोफिलैक्सिस के साथ एमडीटी को मजबूत करने से हम हैनसन रोग में तेजी से गिरावट प्राप्त कर सकते हैं और लगभग शून्य संचरण तक पहुंच सकते हैं।

Ao reforçar o PQT com quimioprofilaxia pós-PQT para todos os pacientes com LL, podemos alcançar um rápido declínio na hanseníase e atingir transmissão quase zero.

En renforçant la PCT avec la chimioprophylaxie post-PCT pour tous les patients LL, nous pouvons parvenir à un déclin rapide de la maladie de hansen et à une transmission presque nulle.

Al reforzar la MDT con quimioprofilaxis post-MDT para todos los pacientes con LL podemos lograr una disminución rápida de la enfermedad de Hansen y alcanzar una transmisión casi nula.

References

1. Tonglet R, Pattyn SR, Nsansi BN et al. The reduction of the leprosy endemicity in northeastern Zaire 1975/1989 J.Eur J Epidemiol. 1990 Dec;6(4):404-6.

.

2. Li HY, Weng XM, Li T et al. Long-Term Effect of Leprosy Control in Two Prefectures of China, 1955-1993. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1995 Jun;63(2):213-221.

3. Li HY, Pan YL, Wang Y. Leprosy control in Shandong Province, China, 1955-1983; some epidemiological features. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1985 Mar;53(1):79-85.

4. Balagon MF, Cellona RV, dela Cruz E et al. Long-Term Relapse Risk of Multibacillary Leprosy after Completion of 2 Years of Multiple Drug Therapy (WHO-MDT) in Cebu, Philippines. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2009; 81, 5: 895-9.

LML - S Deepak, B Naafs, S Noto and P Schreuder

LML blog link: http://leprosymailinglist.blogspot.it/

Contact: Dr Pieter Schreuder << editorlml@gmail.com

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "Leprosy Mailing List" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to leprosymailinglist+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/leprosymailinglist/7940df0c-ea38-4c83-b764-bdd74ede5dbc%40googlegroups.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment